There was room for disagreement in this church. The late medieval church was built on the idea of consensus, community, and history, not upon specific doctrines. Nowakowska's thesis is that Lutheranism was not initially seen as being outside of the church. It is divided into four sections: an introduction (where Nowakowska connects her findings to Europe more broadly), a brief narrative of Protestantism in Poland, a section that focuses on specific episodes within that history, and an analysis of the language used to describe Protestants and Catholics in her source base (which is around five hundred documents). The book sets out to understand why Protestantism was tolerated in this period.

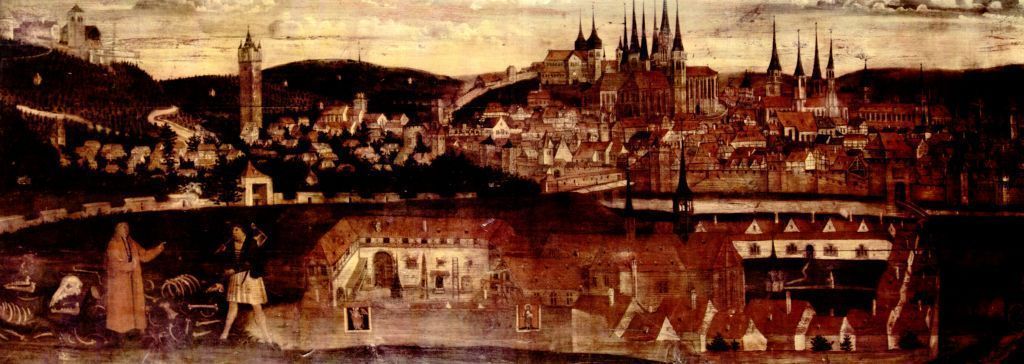

King Sigismund of Poland and Martin Luther by Natalia Nowakowska focuses instead upon religion, specifically the question of Protestant toleration in the reign of Sigismund I, up to 1540 (a date after which there was a new generation of religious and political figures in Poland). Pocock, it proposes a broader hypothesis on the Reformation as a shift in the languages and concept of orthodoxy. Building on John Bossy and borrowing from J.G.A. Instead, through close analysis of language, it reconstructs the underlying cultural beliefs about religion and church (ecclesiology) held by the king, bishops, courtiers, literati, and clergy - asking what, at heart, did these elites understood 'Lutheranism' and 'catholicism' to be? It argues that the ruling elites of the Polish monarchy did not persecute Lutheranism because they did not perceive it as a dangerous Other - but as a variant form of catholic Christianity within an already variegated late medieval church, where social unity was much more important than doctrinal differences between Christians. Polish church courts allowed dozens of suspected Lutherans to walk free.Įxamining these episodes in turn, this study does not treat toleration purely as the product of political calculation or pragmatism. King Sigismund's realm appears to offer a major example of sixteenth-century religious the king tacitly allowed his Hanseatic ports to enact local Reformations, enjoyed excellent relations with his Lutheran vassal duke in Prussia, allied with pro-Luther princes across Europe, and declined to enforce his own heresy edicts.

It offers a new narrative of Luther's dramatic impact on this monarchy - which saw violent urban Reformations and the creation of Christendom's first Lutheran principality by 1525 - placing these events in their comparative European context. The first major study of the early Reformation and the Polish monarchy for over a century, this volume asks why Crown and church in the reign of King Sigismund I (1506-1548) did not persecute Lutherans.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)